Dick Saxton ANARE Club representative

Icebird 1985 – 1986 season

To revisit your old station, now disbanded, after an absence of 21 years is a memorable occasion which only a few are lucky enough to experience.

The opportunity arose quite unexpectedly for a visit to Antarctica on the Ice Bird. lt was also fortunate that this particular voyage was headed for Casey, which is within

3km of Wilkes station built for the IGY year of 1956 by the USA. The Antarctic Division subsequently managed it, and stationed a number of wintering parties there up until 1969.

It was not without some apprehension that I received the good news, as the vessel was scheduled to sail from Melbourne on October 20, which would take us into the

Antarctic waters very early in the season. So early, in fact, I could imagine this wonderful opportunity being embattled in the sea ice far from the continent, and the

opportunity to revisit would be lost. These fears were supported by the pre-embarkation notices from the Division giving arrangement details in the event of the

ship being held up bythe pack ice far from the Continent.

The preliminaries all had that familiar ring — the notices from the Division, the forms and the medical exams, the notification of medical appointments in some cases (because of slow arrival of mail) being received after the due date – but a phone call to Kingston and a friendly voice at the other end set out about sorting out the problems.

On the wharf that Sunday, 20 October, there was the large crowd, some excited, others their pride tempered by realization that there would be a long separation. There were no speeches by members of parliament, right on schedule we slipped the mooring ropes and were on our way.

The voyage experienced less heavy weather than one would normally expect, although we did record rolls of 35° with the largest being 45°. There was the usual

sweep for the first sighting of an iceberg, and at about 60° we were in light pack ice. Apart from a few areas of relatively thick ice the Ice Bird had little difficulty during

the following four days in reaching Casey. Our initial fears of being blocked by the ice were allayed.

It was on October 30, whilst in heavy pack ice that we assembled on deck as the ship heaved-to for a memorial service for Stephen Bunning who had died the previous

night while being rescued after an accident from Davis by the USA Airforce.

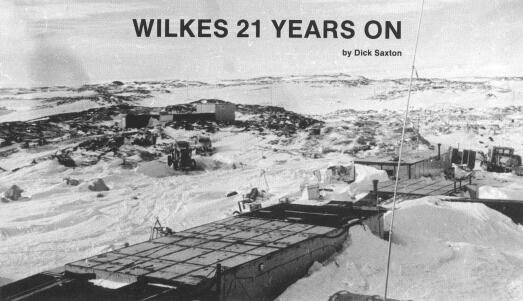

The winter snow was still heavy around the rock outcrops and Casey Station. The ship was driven bow first into thick ice about one kilometre from Casey. Wilkes, while not far away, cannot be seen from this location, apart from the fibreglass radiosond dome standing on a rocky ridge, as it has done for 25 years.

Members of the wintering party were soon out across the ice to visit the ship, and we, in turn, disembarked on to the sea ice and made our way to Casey Station. The

weather on this day, Thursday 31 October, the Met. fellows had ordered one of those perfect days – cloudless skies, full sunshine, no wind and temperature only about

minus 13°C. What a welcoming return!

A changeover at a station is always uncomfortable for the old wintering party, and bewildering for the newcomers, but everyone co-operates and we, the round-trippers, were shown over the station. A young fellow, who apparently heard that I had been a member of the Wilkes wintering party, held out his hand and said he was very pleased to meet me, as he thought that members of the old expeditions probably were not alivenow!! I don’t think he had a chance to meet Graham Chittleborough who had wintered on Heard Island in1949, and who was also doing the round trip and still very much alive!

We managed a short walk of about a kilometre across the sea ice to Shirley Island to the Adelie penguins rookery, where a number of Crabeater seals were sleeping in the warm sun. Some of the penguins objected to our intrusion, but I told them not to be so touchy as I had met most of their grandparents!

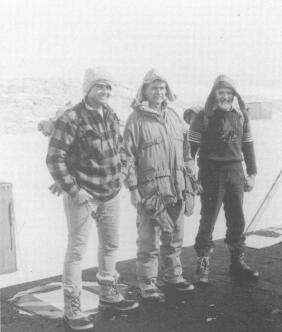

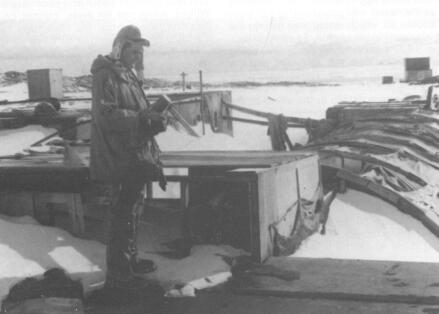

A short helicopter flight took three of us across to my old station which was nestled down in the snow, the scour lines clearly showing the direction of the wind and blizzard. I walked upto the fibreglass radiosond tracking dome, still standing and free of snow. Then across to the fuel tank platforms (some of which we had erected), but the neoprene collapsible containers were now missing or deflated. Next across to the station complex, and onto the roof of the recreation hut and the garage opposite. Because the snow was level with the flat roofs we were

walking from snow level to roof level, just as it was when we lived there. Here on the science block, just about the spot where I had a corner for my office, photographs were taken of the three of us — John Smart, the out-going OIC, and Barry Martin, the incoming OlC for Casey, 1986.

We were able to look through the skylights which had provided that much appreciated light whenever we had been snowed in, as was often the case at Wilkes. Unfortunately as many of the skylights were now broken, the station was almost full of snow, and it was impossible to easily enter any part — a pity, a refuge lost.

Through the skylight of the science building one could see the snow about halfway up. There was an adding machine, a valve radio set, a large radio transmitter valve and odd pieces of typed paper. lt was in this area that Steve Grimsley in between his auroral and other scientific work spent many hours producing the station’s monthly periodical, “The Wilkes Hard Times”. This was a major boost to the party’s morale. Contributions came from every member, and we also had three people who were no mean cartoonists, Steve himself, Fred Spence and John McKenzie, who ran a series on “Mr lntrepid” and all the predicaments he got himself into throughout the year. John was the radio technician in Chompers Currie’s team, which gave us our radio reliability throughout the year.

(Left) Wilkes, 1968, (Above) Entrance to “Fort Knox”, Wilkes

The sleeping quarters were completely full of snow which had entered through the broken skylights. I crossed to the Mess Room with its bar and lounge where we would congregate about 1700 hours for a glass or two wine. From memory, four bottles a night, if the twenty-three of us were in the station, but mostly only about fifteen were ableto be there. At times two and sometimes three field parties were out at the same time, leaving the station with only eleven people to carry the full manning responsibilities. This was the time of the day when we all

tried to make an appearance before dinner.

It was into this lounge that we entered on return from our field trips. l can remember so vividly on return to the station walking into a brightly lit warm lounge with smiling, happy, welcoming faces – the good-natured rude remarks about our dirty clothes which we had worn for over three months. It was a pleasure to remove the wristlets and other gear which had become a part of us, and then, of course, a hot shower and a change.

We normally restricted ourselves to one short shower a week, but on return from field trips it was a great pleasure to have more of a soak. A few had showers more frequently, but like Eddie Davern they had earned the additional use of water by carting their own supply from the melt lake. We had two washing machines and a dryer which could be used when the limited power was not required by the cook.

Just beyond the deep wind scours lay the carpenter’s shop where not onlythetraditional carpenters’ work was carried out, but other kinds of endeavour such as cleaning the blubber off seal skins, and preparing skis for our outdoor activities. Probably it was Peter Ormay‘s great enthusiasm that made the shop a centre of such activities.

Nestled down in the snow was the small power house building containing three 100 kW caterpillar alternator sets, two of which supplied our power needs, the bulk of the power consumed by the stove and the radio transmitters. Heating was by oil in the various buildings. During winter when one alternator was down for overhaul, another had a fault, and the third tripped on overload. There was complete darkness and silence, apart from that familiar humming of the guy ropes from the strong wind. The darkness was soon pierced by shafts of light from many torches as people emerged from their places of work to find the cause of the station shutdown.

Furthest from the huts was the radio shack, small and friendly, where we would gather in small groups at various times, for this was our direct contact with the outside world. It was snug there, whether there was a blizzard above or just plain cold outside. The radio operated from early morning through till 0300 hrs. the next day. The shack was also the contact for us, or rather Ivan Thomas, when we were out in the field. It was through there that we heard of President Kennedy‘s assassination on 23 November, 1963. l have heard it said that most people can remember where they were, and what they were doing on that sad day. We, Malcolm Kirton, Kevin Gleeson, Ivan Thomas, Vic Morgan, Fred Spence and myself were at Lat. 69 508., Long. 114 25E, Min temp minus 41 °C, minus 34°C when we received the news. We were repairing the Nodwell which had lost a front wheel in the heavy going over rough sastrugi

terrain.

The station was always warm. The sleeping quarters were 11°C. The work areas were kept at about 15°C and the galley was frequently considered too warm; the temperature probably reached 25°C because ot the stove. The corridors received spill~over heat from the attached buildings but it was cold enough to produce an interesting array of ice crystals, stalactites which would during a heat wave (a slight rise in temperature), drop on us, and the knobs of ice on the floor like stalagmites formed slippery and dangerous obstacles when walking.

Only the memories of the huskies remained. I walked up towards the old transmitter hut stopping at the patch where the 16 huskies were once tethered.They spent the whole year in the open. It was always a spot for expedition members to pause as it was not the thing to do to ignore the huskies who expected a pat. Once I started off before giving a dog what he considered his due patting, and as I moved I found he was gently gripping my parka in his mouth as if to say “you owe me a few more minutes”. Mukluk, our only bitch, had a litter and two

pups survived. Those fluffy pups also received much attention, and of course gave much pleasure until Christmas, when the ham after cooking was put out to cool. One can guess what Dick Ritchie, our cook, found out about his ham. Malcolm Kirton, who looked after the dogs through the year, was fortunately on traverse over the summer period!

There was good natured rivalry between the dog handlers and the diesos, or, probably more correctly between Malcolm and Geoff Wilkinson. The dogs were harnessed and usually away beforethe vehicles could be started, but then the dogs ignoring commands because they were so excited, would finish up either side of a guywire and immediately blame each other. The fur would fly with snapping and biting, an unholy mass of twisted traces, and equally furious dog handlers. By this time the vehicles would splutter into life — the result a draw!

Clearly visible was the route to the plateau, now named Law Dome. The Pimples, two small snow hills, marked the opening through the rocky moraine. Here in 1962 I met Bob Thompson and his team on their return from their epic trip to Vostok. We took over the running of Wilkes station and in turn used the same route for our field trips to the plateau. The D4 Caterpillar tractors, (now being restored for an Antarctic museum) laboured up the slopes with their sledges behind, between the Pimples, and we were off.

The ANARE club has a conservation policy which was published in the March Aurora 1985. One of my briefs was to report on the Station’s conservation as it related to this policy. l suppose, as in most reforms, there is a group who expect their ideals to happen immediately. Having experienced some of the difficulties, one should not be unreasonably critical of the stations. Man‘s intrusion everywhere is inevitable, and that intrusion must cause some imbalance as italways has. It is important however, to realize this, and in this case to take precautions so that the disturbance is reduced to a minimum. It is in this context I observed the conservation impact of the area.

I

It is a pity to see the Old Wilkes station so viable in the past, just deteriorate, whereas at the time it would not have been very difficult to select sections and maintain these ice free, progressively removing surplus gear.

The old food store etc. could well remain. Food was stacked outside but the labels were faded, giving little clue as to the contents. A considerable amount of old equipment was buried in the snow, but this could be progressively removed during the summer when there is a certain amount of thawing. Partly collapsed aerials make the sight appear very untidy.

The extensive rebuilding program at Casey is accompanied by a large amount of materials being stored over a wide area. As the building program proceeds to completion, much of this will be used, and surplus or redundant equipment removed.

More importantly, I feel, is the attempt to maintain the integrity of certain selected areas, rookeries, flora etc. In a series of talks and illustrations on the ship these were defined and discussed with a view to having everyone understand and appreciate the reasons. From my understanding, this was very well done by Rod Seppelt in a manner which would make people feel they wanted to be part of the conservation plan.

The 1986 expeditioners, how did they differ from those of twenty or more years ago? I cannot think of a more pleasant team with whom to sail, and I would imagine to winter with them would bring no regrets.

The cameras, cine, 35mm and video, were all a far cry from those carried by expeditioners of the past.

Another difference is that the expeditioners wintering these days are both male and female. I cannot do more than report on what I saw, and that each person acted as an expedition member willing to do their best. Whilst in the past expeditioners were an all male affair, the fact that women were on the ship and station did not seem at all out of place, in fact it seemed quite natural, and I expect that is an accepted opinion of all expeditioners.

A successful and happy year can usually be judged by the decorum of those being relieved. Often the bravado on going down, probably covering a hidden apprehen-

sion, has matured in the ensuring 12 months.

A difference (and as far as I am concerned it was a enormous difference) is the navigational aids. The Ice Bird operating on Satellite navigation knew accurately on a continuous readout the exact position, speed and drift. This concept is extended to the traverse parties. There is not that long period of travelling on dead reckoning before one gets a hazy glimpse of the sun to

obtain a fix. Vehicles use radar to pick up stakes which enables them to travel in all weathers and at night. Days were lost in the past because of immobility during those poor visibility periods. It must be a great time-saver to follow staked routes during poor weather conditions.

Neville Collin’s article in December ’84 Aurora reminds me of the simple difficulties we had, such as answering a call of nature in the open in a blizzard – hanging on until finally one has to give in! I can remember Ivan Thomas being most indignant at having his backside iced up. ln the biting winds one could not tell when one had started or stoppedl! The present tractor trains with mobile heated shower room and washroom would be a very welcome improvement. This is all possible because of larger vehicles carrying power units which run continuously.

l have heard it said that the past expeditions were more of a “boy scout affair”. It would be an interesting study to compare the input in men and money of say 25 years ago, with that of today. and compare the research or technical output. Rod Mallory, the American Meteorologist, who headed the American team of three with our 1963 Wilkes party, expressed the view that the Australian clothing issue per person was considerably less than that supplied to them but it was nevertheless considerably better. He also expressed the view that dollar for dollar

the work of ANARE gave a better return than that of the American expeditions. Could we compare the past with that of the present? It would be interesting, even though there are so many factors which could make some of the findings interesting but not conclusive.

ln the past, with the smaller wintering parties, all members were expeditioners, in that nearly all members took part in essential field activities. There was not the more defined demarkation of field party (Traverse Party) and station party. The OIC, I believe, was expected to be involved, and in every case I know was most anxious to take part in field work, whereas now the emphasis rests more with station management.

My brief from the ANARE Club was to observe and report on the following:

(a) Conservation and its relation to the Club‘s

conservation policy.

(b) The new buildings at Casey.

(c) The relationship between the building personnel and

other expeditioners.

I have dealt with conservation. The new building program at Casey is certainly a very large and difficult undertaking with difficult logistics. Some of these problems happen on most construction sites, but in such remote conditions much of the difficulties are greatly increased. The buildings are enormous compared with the traditional Antarctic Stations. The two-storey

buildings dominate the landscape. They are well constructed; much thought has gone into the design. One could possibly go South and remain in a climate much milder and more stable than that of Melbourne or elsewhere, unless they sought to venture beyond the confines of the Station.

From what l saw of the D.H.C. teams who work on the buildings, they were all most conscientious about doing a good job. In a situation wherethere are so many people, it is to be expected that those working together will have a tendency to spend their leisure time together, and this probably causes more division than any intentional separation. Probably personnel should realize this, and try to counter these very normal tendencies.

ln conclusion, l would like to express my thanks to the ANARE Club for their support, and in particular my appreciation to the Director of the Antarctic Division, Mr.Jim Bleasel, for making this opportunity available to the Club. lt was a much appreciated experience.